This is The Diane Project

Plus: Elissa Strauss on how caregiving makes you interesting

Hey there! If you’re new to The Diane Project, here’s a quick overview. I’ve completed one season of TDP and posted six stories. You can read them in order by clicking the “Next” button at the end of this story. If you prefer having me read the story to you, click the play button in the widget above. You can also subscribe to TDP as a podcast. — Aaron

Welcome back, longtime readers. Everyone else, glad to have you. Without further ado, may I introduce the star of our show.

Diane is my wife of 29 years, the woman to whom I owe everything, and as I write this she is sitting beside me on the couch, snoozing peacefully. It’s midnight in the high-ceilinged main room of our small contemporary house, located half a mile north of the border with Chicago.

If I were to step outside into our alley and walk to Custer Street, I could see the brick building where we met in the winter of 1990. It’s a former taxi dispatch station that was bought by a bunch of thrifty Mennonites and turned into a church. Five years after we became friends, we got married there.

In the fall of 2020, my bride was diagnosed with Lewy body dementia. Diane always told me her mother was at her best in a crisis, and in many ways she is her mother’s daughter. Our response to this devastating news was to snap into action.

We had moved to Kansas City in 1997 and were living in a beautiful old Arts and Crafts house. We loved that place, but we knew the time had come to sell. Diane was not only experiencing cognitive loss, but eventually she would develop Parkinson’s symptoms as well. Lewy — it’s two diseases in one.

One morning over coffee, Diane announced that she’d woken up with a word on her mind. The word was Evanston. I knew exactly what that word meant: We would go back to Illinois to live in the community surrounding the brick church, the most caring community we had ever known. I was all-in. The housing market was tight, but with some allies and imagination we made it happen.

And now here we are, on the couch. Lately Diane has been waking up in the night. I don’t know why and she can’t tell me. But I’m on the case. Since 2022 I’ve been her full-time caregiver and I’m not so terrible at it anymore. Using trial and error and calls to our palliative-care nurse, I’ve come up with some options. Tonight we had a win.

I should celebrate by crawling back into bed, but I linger a while by her side, listening to her breathe, savoring this moment. Forest rangers like to say they are paid in sunsets. Moments like this are part of my compensation. The biggest reward, though, is knowing that Diane is safe at home and that I’m making life as pleasant for her as I can.

I’m a former television critic for the Kansas City Star and Primetimer. Diane was a senior editor in educational publishing before her midlife pivot to history. She earned her master’s degree and finished her first book in 2007. Five years later I quit the newspaper to go into business with her, giving talks and publishing books on American history.

We met and married at Reba Place Church in Evanston, Illinois. Reba is an intentional community with a rich and unique subculture. After 25 years in Kansas City we returned to Evanston and built an accessible house in the backyard of a Reba-owned property.

Those two paragraphs were written on March 13 — more than seven months ago. Since then I have been trying to launch a newsletter about caregiving. I’d like to say that actual caregiving duties kept getting in the way, but that’s not true. The first three years after diagnosis were very challenging. I had to adapt to a progressive disease while downsizing and moving and building a house. But the dust has settled on all that, and I now have great care providers who come in during the day. So I have the time and headspace for this.

The struggle, rather, has been trying to write without the help of my muse and my best editor. Diane and I were a team from the start of our marriage, and it was a great day in 2012 when we began working together. After her diagnosis, we talked about maybe creating a podcast or YouTube channel about our Lewy journey. Always thinking ahead, Diane told me that if she couldn’t take part in the project, I could do it without her, on one condition: I had to preserve her dignity. As Bill Maher would say, that is literally the least I could do.

Long story short, I overthought this project, and as a result it took way too long to launch. I tried out a bunch of concepts and even designed a few logos (a fantastic way to kill time) before coming up with The Diane Project earlier this month. Well, at least I have a long list of story ideas now, as well as a clearer idea of where I’m going.

And hey, we’re 800 words in and you’re still reading, so that’s a win.

***

It took me two years to admit to anyone that I was a caregiver. Even then I had no idea that I had joined a huge invisible army of caregivers until I started work on this newsletter. Roughly 42 million Americans provided unpaid care for an adult over age 50 in 2020; that’s up from 34 million in 2015.

At least 11 million of us are taking care of someone with cognitive loss. On average each of us provides 1,000 hours per year of care, at the expense of paid work, relationships, mental health and sleep. Dementia caregivers willingly make these sacrifices to keep their loved ones out of institutions. One study found that 90 percent of those living at home with neurocognitive illness had an unpaid caregiver.

Caregiving has been around as long as humans have been around. But many observers say we’re in a caregiving crisis now, owing to broader social trends.

First, folks are living longer. Older couples wind up having to take care of each other, and when one of them has cognitive loss, the stress can become too much. Or if they have a child nearby, she (it’s almost always the daughter) finds herself sandwiched between caring for parents and kids at the same time. These caregivers are exhausted and suffering for lack of support.

Second, we spend more time alone than previous generations. Thanks to lower marriage and birth rates, there are more single-person households in the U.S. than married-with-children households. Being alone is bad for your health, as numerous studies have shown. Covid only made things worse.

Loneliness is a double whammy for dementia. It’s adding to the number of people living with cognitive loss and making it harder to find caregivers for them.

“Humans used to be surrounded by more people, family and non-family,” writes Elissa Strauss. “They used to be more invested in community, which curtailed loneliness and benefited care. When we are other-directed, we place more value on acts of togetherness, including care, and we also invest more time and energy into caring for the caregiver and sharing the burdens of care.”

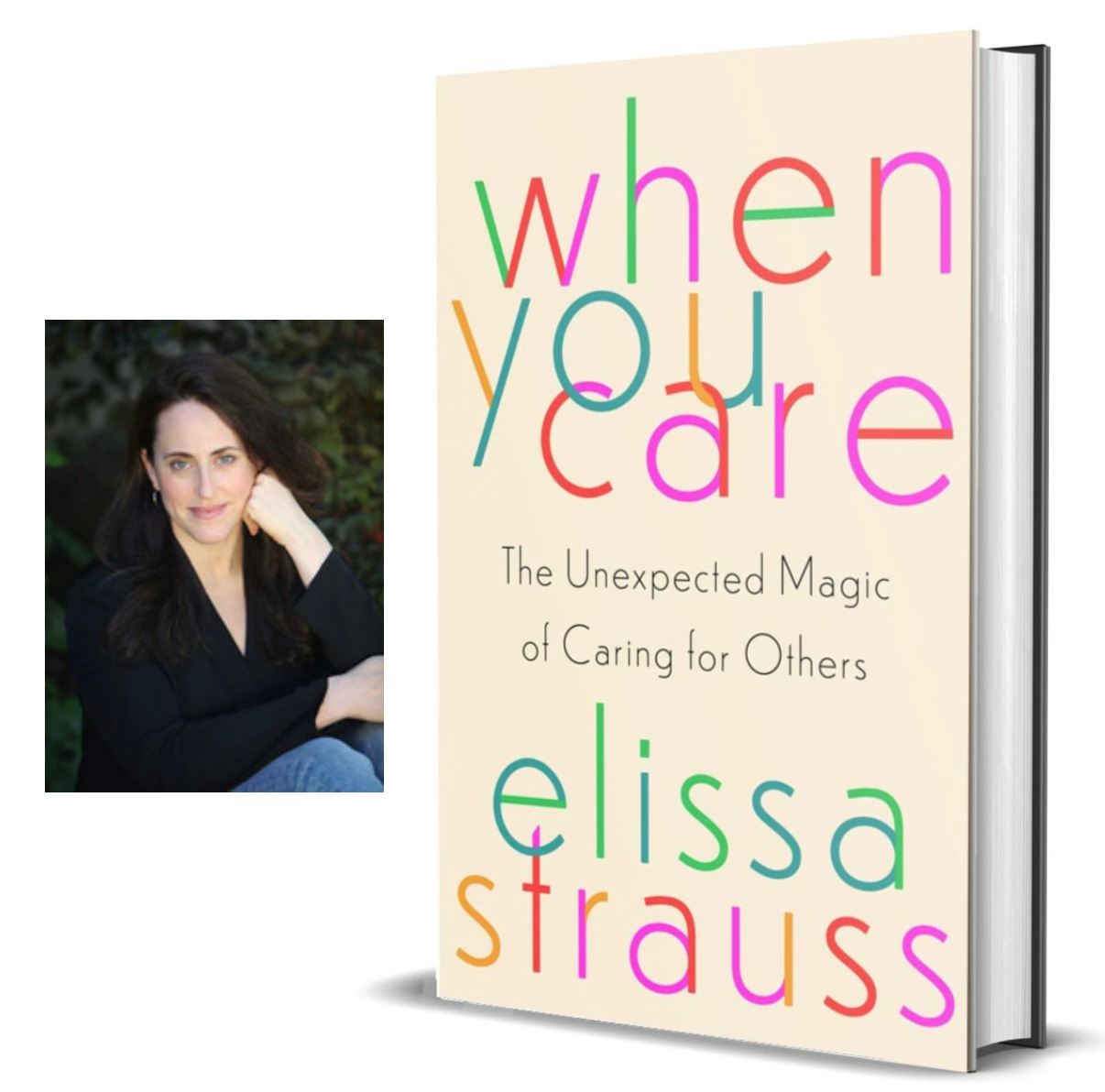

Strauss is the author of When You Care: The Unexpected Magic of Caring for Others, which I loved so much that I called her up for my first author interview for The Diane Project.

Like me, Strauss sees the caregiving crisis as something that needs to be addressed both “from the top down and the bottom up.” Top-down policy changes will be slow in coming, so all of us “need to work on creating new narratives around, and understandings of, care.”

For too long, we have treated caregiving “as an obstacle to the good life” rather than “an essential part of a meaningful one, individually and collectively.” Strauss asks,

“What if we saw caring well as more than obligation? What if we also saw it as a privilege, opportunity, and right? That will only happen when we acknowledge the power of care.”

Strauss has written about caregiving for The Atlantic, New York Times, Glamour, Elle and Allure. Yet it wasn’t until she became a new mom that she had to face her own negative feelings about leaving the workforce to take care of others. That led to the reporting that produced her new book and Substack.

“When I dug into research about care’s effect on our health, I discovered that in the right conditions, caring for others can be very good for you both physically and psychologically,” Strauss told me. “Caregiving is now being associated with longer lifespans, lower inflammation and finding one’s life meaningful. It is also associated with lower suicide rates among men. Unfortunately, we need to keep fighting for these right conditions.”

I appreciate that Strauss includes dementia care in her book alongside more socially accepted forms of care, like motherhood. The reality, though, is that cognitive care is something a hypercognitive society devalues because the thought of losing brain function fills most people with existential dread.

Who can forget Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel, defender of Obamacare, arguing that people over 75 should forego extraordinary medical treatment (i.e., die as soon as possible) because they are “declining” and “no longer remembered as vibrant and engaged but as feeble, ineffectual, even pathetic”? This is a huge bee in my bonnet, and I’ll return to it in future editions of TDP.

I interviewed Elissa Strauss in … (checks notes) … late May. Here are the edited highlights.

The reason I latched onto your book was the tone. It’s there in the subtitle: The Unexpected Magic of Caring for Others. A lot of journalism around this topic of caregiving is simply alarm-ringing: reporting out some numbers, telling stories about overwhelmed caregivers, then quoting a few experts who echo the journalist’s narrative which is, “another huge crisis that can only be solved by government.”

Elissa Strauss: We have to be catastrophic about everything to make any noise. Obviously we need more caregiver support in this country. There's no question about it. But I think it's a real lack of imagination when we deny that care is this thing we do. It's part of our lives. It’s always going to be inconvenient, but we need to accept it as part of our lives and stop trying to fight it.

We may never get the government support we actually need until we also have a cultural conversation about what does it look like to put care back in the center of the human story. It’s been systemically left out, not just of our economy, our GDP, but excluded from our pulpits, whether at church or synagogue or mosque. Until we widen the aperture of care, and learn how to mentally accept caregiving as part of life, I'm not sure we're really going to figure out the practical solutions.

How did motherhood get you interested in writing about caregiving as a practice, not just a policy matter?

Strauss: I was writing a lot about the lack of structural support mostly for parents, but also for caregivers as a whole. I wasn't ambivalent or conflicted about having kids, and luckily I didn’t struggle with postpartum depression or with connecting with my child. But I did have this fear that motherhood would make me less interesting, less relevant, less cool. And it took me a beat to realize that, while I was writing about how our culture didn't value care, I myself did not value care. I lacked curiosity about care. And I thought, how could I sit there and complain about how no one respects care when I myself really didn't respect care?

I think we generally know infanthood as a time of deep dependency. We're not shocked when we bring home our babies and they are dependent on us. That expectation is built in. At the same time, people are totally shocked by motherhood! Fifteen years after you leave your childhood homes in a state of total independence, you get put in this situation in which human dependency inserts itself in your life and it feels like an assault.

My experience caring for my sons has been profound — in psychological terms, in spiritual terms, in philosophical terms. And the more I spoke with other caregivers, the more I realized there's so much richness and wisdom that comes from the experience of care.

The way we parent in this country is like the way we care in this country, so siloed, so alone with not enough support, often with our financial security at risk. That is terrible! But until we pull care into our narratives of who we are and how we live in this world, we're not going to have the conversations we need to get that practical support. And we're not even going to really understand what kind of practical support will actually serve us as caregivers.

So often care is just flattened into portraits of either saintliness or burden. It's these two poles of, “Isn't it so wonderful? This person's so giving,” or else we're totally wiped out. If we just flatten care and treat it as pure burden, we're not doing care any service at all. At all. I think about how we talk about our relationships with our friends and our spouses when it's not a care relationship. We allow for so much complexity and richness and tension and friction. These things are all fundamental parts of human relationships, but not when it comes to care.

Caregiving is filled with friction, but that friction can be generative and productive and illuminating. It can also be depleting and challenging without benefits. On the whole I think caregiving makes you interesting. But you would never bring it up at a dinner party. If someone hikes Mount Everest, everyone's like, “Ooh, tell me everything. What was it like?” But if someone's caring for a partner with dementia, no one wants to hear this. Why is one human challenge so elevated in our culture and the other human challenge so diminished?

You write about being a stay-at-home mother and how those first four months were especially hard — but then, once you got through that, there was this reward. You were emotionally, intellectually, linguistically bonded with your child. You had a stake in their future. With dementia, it's literally the reverse. Your loved one loses their intellectual ability, loses their language. They may even lose their emotional bond with you.

You see this reflected in public attitudes. Let’s say there was a mother and a child in a park you were walking through. And then at the other end of the park was an adult child with his mother who had dementia. These are both caregiving situations, but people’s responses to them are totally different. How do we get past that?

Strauss: We need to put front and center the reality of dependency in our lives. Most of us spend the majority of our lives on one end of a dependency relationship. And in the book I tried to speak to as many different caregivers with as caregiving experiences as possible to include those stories. I certainly didn’t want to idealize or romanticize it, but I wanted to make space for the fact that people had positive feels. They felt so good about being able to just give love and care to these people they loved, even when their cognitive ability declined.

I spoke with a man who had conflict with his father his whole life, huge political differences — a cranky, judgmental father, according to the son. When the father got dementia, there was a softening that happened. And actually it was very healing for him. These are voices that are trying to show that dementia can be a lot of different things. I have a close friend, Courtney Martin, whose father has dementia. She writes about caring for him with such tenderness and openness that I'm crying every time I read it. But I am also shocked that I've almost never heard this. This is not the story we hear.

Someone I interviewed in my book spoke about how he took his wife with Parkinson's to restaurants. And sometimes people would say he was a hero, and he didn't love that, because he didn't feel like he was being a hero. Other times, people would make him miserable because someone with Parkinson's is not our idea of an ideal diner. That's just messed up. That's a culture that's in denial of the fact that human bodies aren't always working exactly how we want them to, and it needs to change. It's not going to make it all better, but getting rid of that taboo could certainly help.

***

Reading over my interview with Elissa Strauss, I realized that something she said had a lasting impact on my own life.

It was when I asked if there was any low-hanging fruit that we could go after while we waited for Congress to get its act together. Strauss thought of two things.

First, private employers could put an end to the practice of scheduling employee shifts at the last minute. “If you’re a parent or have to care for an adult parent with dementia, how can you ensure they’re cared for while you’re working if you get your schedule at the last minute?” she said.

Her second suggestion cut me to the quick.

“I would love for institutions to do more to make space for people who are dependent as well as their caregivers,” Strauss said. “My synagogue makes a point that, if you move slowly, if you think slowly, you are welcome at our synagogue. In fact, there are all kinds of people who go up to the bema to help the rabbi lead the service. People with cognitive disabilities, people with physical disabilities — if it takes them a long time to get there, no one's in a rush. When you really make space in a society for people who are dependent, it liberates everyone from this myth that only people who are independent can participate in society. The way that affects the caregiver, we cannot overstate that.”

At my church, we also have a lot of audience participation. It can take the better part of a minute for someone to get from their seat to the microphone at the front. This slowing-down of the service was driving me batty. The old man in my head would shake his fist at the sky and yell, “They know it’s their turn, they know they’re slow, why don’t they get up sooner??”

As soon as Strauss mentioned this exact tendency in her synagogue and how they dealt with it, I realized I had to do a reset. I saw, for the first time, that my impatience at church was being mirrored at home. As a caregiver I was often moving too fast for my wife and I needed to slow the F down, for her sake. Learning to appreciate slowness is a gift, for which I’m grateful to Elissa Strauss.

You can order When You Care: The Unexpected Magic of Caring for Others using my Bookshop.org link. All proceeds of Bookshop sales go to the Robert H. Levine Foundation, which my friend Barbara Levine began in 2022 to aid Lewy body dementia research.

Land of Linkin’

Now that I’m back in Illinois, I get to revive the Internet’s oldest pun.

We love our high-performance house and low energy bills. Sadly, voters just aren’t that interested in climate change according to YouGov (a highly rated pollster).

Hallmark’s being sued for age discrimination by its former casting director, who alleges the TV channel wanted to replace Holly Robinson Peete and Lacey Chabert (!!) with younger versions

The Menendez Brothers, convicted of murder in 1996 following a sensational trial, may be set free in weeks after two Netflix series revived interest in their case

In local news, Evanston has the best city water

New rare recordings of Charlie Parker playing “very relaxed” in Kansas City just dropped; my favorite is a 1944 cut of “My Heart Tells Me”

I am ALL-IN for a Jason Kelce-hosted late night show

Sub-2:10 too good to be true? I just ran the Chicago Marathon, where Ruth Chepng’etich shattered the women’s world record. Was it legit? Probably! The Real Science of Sport Podcast analyzes her historic run in detail.

My resource for new caregivers

The Diane Project is a free newsletter. I’m not going to set up a paid subscription. There will be Bookshop links to benefit Lewy body research, and if I ever do finish that book, I’m sure I’ll be hawking it nonstop. But you won’t be under any obligation to buy it. Whenever that is.

Instead, I’m giving away a resource to encourage people to join The Diane Project mailing list.

If you or someone you know is starting on the journey with a loved one who has a neurocognitive illness, this is the guide that I wish I had when I was starting out.

When you subscribe, I’ll send you an email with the link to the guide.

If someone you know is starting out on the care journey, I’d be grateful if you forwarded this email to them, or just pointed them to The Diane Project.

(If you’re subscribed already, you should have gotten an email from me with the link to the guide. Hit me up if you didn’t.)

Endnotes

I’m aiming for two to three newsletters a month.

I have likes and comments turned off for now. You can reply to this email or click here to send me feedback.

All of our books are for sale.

You can show your support for TDP by donating to the Levine Foundation. Barbara Levine, who also started the Lewy spouses’ support group that I belong to, is a tireless advocate for Lewy education and research.

Thanks for reading,

Aaron