First of a three-part essay on my wife’s midlife reinvention.

When we were dating in the early ’90s, Diane lost the central vision in her left eye. This can happen with high myopia. At the time she was a senior editor at an educational publishing firm in Evanston. Vision loss could be both personally and professionally devastating to her. So when an eye surgeon proposed scarring the macular tear with lasers, of course she said yes.

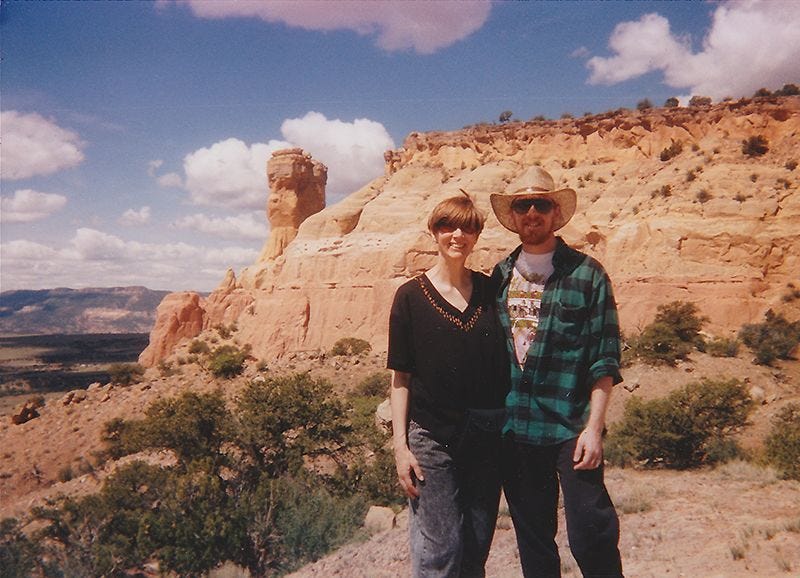

Those procedures proved to be not only excruciatingly painful but quite useless. The only positive takeaway from the ordeal was that it seems to have convinced Diane that I was the real deal. She was a 50-year-old divorced mother of two, and I was her 28-year-old boyfriend. It couldn’t possibly last. “You won’t want to be married to an old woman,” she predicted (wrongly, it turns out). But hadn’t I driven her to every eye appointment? Hadn’t I sat in the room as she endured these laser procedures? And waited on her hand and foot afterwards?

In traditional wedding vows, two people say they will have and hold each other “in sickness and in health.” It’s a caregiving pledge. I had made good on my end, and in due time she would return the care.

Of course, being a modern couple we couldn’t just do the trad vows. We also wrote a vision statement. I think we must have copied some of these lines out of a Harville Hendrix book:

“We build each other up, support and affirm each other, and are always there for each other.”

“We live without needing to be in control.”

“We stretch each other's minds and areas of understanding.”

“We laugh a lot.”

“We give each other grace and the benefit of the doubt.”

“We help each other achieve our dreams.”

It went on like that for most of a page. To our credit, we took these promises seriously. Every so often we would pull out that statement and review how we were doing.

Sometimes we might even flip the page over and see these goals we tacked on at the end:

“We have both found a voice, an audience, and a deeply satisfying purpose for our writing.”

“We collaborate on writing projects.”

I’m sure they were put at the end because, at the time, they were purely aspirational. Diane was revising a book for an educational publisher in Wisconsin and I had a secretarial job with a late-night TV newsletter. Sure, it would be great to compose “deeply satisfying” works together. But what? How? I don’t think we had a clue.

Diane eventually returned to work with her one wobbly eye. She also took out a sort of insurance plan, attending classes at night and on weekends to earn a certificate in massage therapy.

After we married, I moved in with her — and almost immediately I asked to quit my desk job and try my hand at freelance writing. I had a newsletter that earned no money. I wrote once a month for the Village Voice and had a couple of contacts in journalism. It was a nervy ask on my part. Still … “We help each other achieve our dreams,” right? She said yes.

Fifteen months later the Kansas City Star came calling. They wanted to hire me as their television critic — paid move, 401(k), health insurance, the whole shebang. Now, I’ll be the first to admit that writing about television was never “deeply satisfying” work for me. But I was good at it. And we both felt a propulsive excitement about my burgeoning career as my byline appeared in ever-more-prestigious publications.

They flew us both to KC, and while I interviewed at the paper she drove our rental car around town. She looked at the nice neighborhoods my editor had told us about and the east side slums that he hadn’t. She gave me permission to upend our world. It was November 1996, and it was the last time I remember her driving a car.

As we were preparing to move, Diane lost the central vision in her other eye. She had been assured years before that macular tears “very rarely” happened in both eyes. Now she couldn’t see five feet in front of her. A doctor in Chicago proposed a Hail Mary — radical surgery on both eyes to remove the blood vessels that were occluding her central vision. This would require complete immobilization for two weeks, so great was the risk of retinal detachment.

Diane tentatively agreed to the surgery. She lined up friends to help with meals and such, since I had to get to Kansas City to start work. But she also found a doctor in St. Louis who was much more of a specialist in conditions like hers and sent him her chart for a second opinion.

One day the phone rang at my desk. I picked up and heard someone in a low voice talking rapidly. Realizing it was the doctor in St. Louis, I grabbed a pen and began taking notes. In my experience, he said, some patients see a short-term benefit from these surgeries, but long-term their outcomes are no better than patients who do nothing, I’m sorry to say.

I called Diane with the news. She sounded relieved. But here she was, legally blind, moving to a strange town, couldn’t drive, couldn’t look at a screen. She had agreed to leave Evanston after 20 years, leave friends and family behind, all so I could live the ink-stained life. She was genuinely thrilled for me, but there had to be moments when Diane saw the unfairness of it all.

And yet, my wife is nothing if not resilient and resourceful. Besides, you don’t tell a woman with Nutritional Healing and Your Body Believes Every Word You Say on her bookshelf that nothing can be done.

One day, I think while in a health food store, Diane found a book on eccentric viewing. This technique, also known as “peeking around the blind spot,” is based on the idea that if central vision shuts down, the brain can be trained to “see” more with the periphery of the eye. Up till then we had both assumed that her vision problem was an eye thing. This book was asserting that it was a brain thing.

If you’ve read Norman Doidge’s The Brain That Changes Itself, you know that the unlimited plasticity of the adult brain is one of the great scientific findings of the past 50 years. But it wasn’t until about 20 years ago that clinicians started doing studies to see if rigorous training could help patients remap their eyesight after vision loss. What I’m describing happened a decade before that.

This new age book on eccentric viewing had a bunch of eye exercises that Diane was supposed to do. She did them every day for hours, until she had to lie down and put a cold compress on her eyes. But in a few weeks she was able to use her computer again. She put a large text magnifier on her desk, supersized the fonts on her screen and kept bright reading lights around the house.

Her eyesight never was fully restored. The way she always described it was to turn to someone and say, “I can see you but I can’t make out your face.” Still, she was able to pass for a sighted person and resume her regular routine. The human brain is amazing.

Back when we were getting friendly, not yet dating, we bonded over history. I would go over to her house for dinner, then we’d watch Ken Burns on TV. So when we moved to Kansas City it seemed natural to learn about the area by visiting all its museums.

One fine day we drove out to the Wyandotte County Museum, hidden away in a park at the edge of the metro. We walked through the permanent exhibit (mostly archaeology, yawn), then wandered into the lonely corner that every county museum has, with the community room and the huge stash of donated things.

Here we found a table with some handmade displays. One of them featured a laser-printed picture of a woman that appeared to be from the nineteenth century and a paragraph explaining who she was. This was Diane’s introduction to the woman who changed her life.

Her name was Clarina Irene Howard Nichols, and we learned that she lived in Wyandotte County in the 1850s and ’60s. She had been a newspaper editor in Vermont who counted as her friends Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. She was an early figure in the woman suffrage movement that started at Seneca Falls in 1848, becoming a popular speaker on the circuit. Then, in her forties, she left it all behind and moved her family to Kansas Territory.

Clarina Nichols was a woman on a mission. Charming herself into the male-dominated politics of her time, she helped secure for the women of Kansas the most liberal set of reforms anywhere in the Union. She was heralded by her peers, memorialized in the early volumes of women’s history and then, like everybody else not named Anthony or Stanton, completely forgotten. Judging from this display, Clarina Nichols was even a footnote in Kansas history.

Diane — also a woman on a mission and experiencing upheaval in midlife — wanted to know more about this kindred spirit. She tracked down the museum’s director, John Nichols, who was working that day, and began quizzing him. A soft-spoken Kansan, John Nichols (no relation) said he had created the display on Clarina because she had been, in his opinion, unjustly overlooked.

Sensing that Diane had more than a passing interest in this pioneering feminist, John showed us to the archives room and introduced her to Steve Collins. A professor at the nearby community college, Steve was there working on his index of the Quindaro Chindowan, a newspaper Clarina Nichols wrote for in 1856.

Steve told us that there had been a scholar who had gathered Clarina’s local writings and published them in the Kansas Historical Quarterly in the 1970s. He was said to be working on a book about her but had since passed away. By the end of their hour together, these two men were urging Diane to write the biography of Clarina I.H. Nichols.

We started with weekend trips to the state archives in Topeka, working through their slim collection of texts and microforms related to Clarina. Research trips would become our favorite form of travel. Besides serving as her driver, I read any texts that she couldn’t and doubled her productivity at archives, which in those pre-digitization days had to be visited in person.

Diane acquired and read through volumes of the Kansas Historical Quarterly, including the eight-part series of Clarina’s writings compiled by the late Joseph Gambone (the would-be biographer). Next we set off in our Honda Civic for research trips to Vermont and northern California, where Clarina spent the last 14 years of her life.

When I told my editor at the newspaper what I was doing with my two weeks of vacation, she asked if Diane would write a profile of Clarina for the Sunday arts section. This would be the first summation of her work and would appear in a newspaper that was read by a million people.

This led to a discussion between Diane and me about how she would sign her article. When we married, our pastors had introduced us as Mr. and Mrs. Barnhart. She began using my last name professionally. But I didn’t like the idea of her appearing in the Kansas City Star as Diane Barnhart. I didn’t want readers to think I was the reason she was getting published — that was Clarina’s doing.

One option would’ve been to use her first husband’s surname professionally. That was what Diane’s sister had done after her divorce. But my wife had no interest in that option.

So that left the name she was born with: Diane Eickhoff. Oh, the places that name would go.

In Part 2 …

Caregiving takes center stage as Diane’s life pivot continues. Look for that next week.

Endnotes

At some point I got it in my head to shoot footage for a documentary (never made) on Diane’s journey with Clarina Nichols. Here’s a short clip of her touring the ruins of Old Quindaro with John Nichols and Steve Collins. Steve is showing her the site where the Chindowan was published. I also made my sweaty bride stand next to the John Brown statue for a while. This Italian-made monument to the storied abolitionist was dedicated in 1911 following a fundraising campaign at Western University, an HBCU that was on the Quindaro site from 1865 to 1944.

Speaking of Harville Hendrix, his Getting the Love You Want is still a great resource for couples at every stage of the journey.

And speaking of our wedding, here is the Robert Bly poem that we put on the cover of our program. The poem presages all the road trips we would take and all the Kansas City monarchs we’d behold.

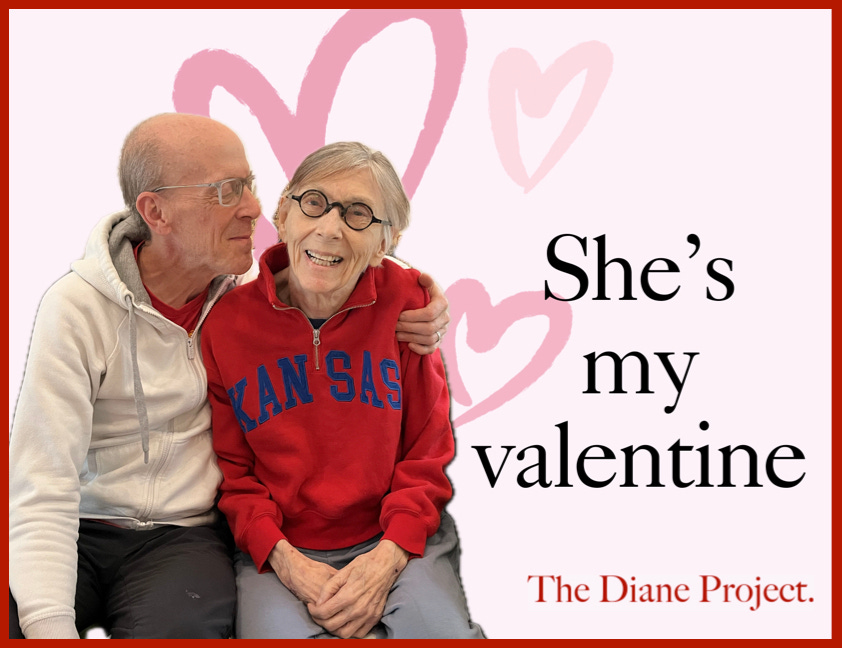

Diane update

Shortly after I sent out this postcard to friends and family, Diane got pneumonia. Turns out we both had the flu, but I treated it like a cold for a few days. When neither of us improved I took her to urgent care, where I was told I’d better take her to the ER. After that she turned around quickly. I’m happy to report that she’s back to her usual self, if not her old self.

I mentioned that we visited museums when getting to know KC. We did it using the Passport to Adventure, a little booklet issued every year to promote the area’s historic and nature sites. Without the Passport I doubt that we ever would have made it out to the Wyandotte County Museum. As of 2024 it was still being published on actual paper.

Land of Winston

I wrote most of this newsletter while reacquainting myself with the music of the late George Winston. His solo piano LPs were part of the soundtrack of my life growing up in eastern Montana. This past Advent I took part in a dance at church that had been choreographed to Winston’s “Carol of the Bells.” Apple’s algorithm (I hesitate to call it “Apple Intelligence”) noted my interest in the song, and a few weeks ago it surprised me with his marvelous 2024 album Eastern Montana, the first of several planned posthumous releases.

Thank you’s

Thanks for shopping TDP’s Bookshop links, which benefit the Robert H. Levine Foundation for Lewy Body Dementia Research. Bookshop now features ebooks.

Thanks for checking out the history titles that Diane and I wrote and published.

Thank you for sharing this newsletter with others.

If someone forwarded The Diane Project to you, consider subscribing. It’s free, with newsletters once or twice a month.

When you subscribe, I’ll send you What Every New Cognitive Caregiver Needs To Do. It’s the guide I wish I had when I was starting on my journey.

Thanks for leaving your thoughts and questions in the Comment area.

Above all, thank you for reading.

Aaron

What a beautiful tribute to Diane this is. Aaron, and I am sure it is already serving to be a blessing for those who are experiencing a similar situation with their spouse or loved one. At the moment, I am reading this because it’s a fascinating story, and I may have friends who could find it useful, but none of us ever really know when a health situation like this could upend our lives. And I am enjoying learning about Diane’s life and work.

Great to read about your life with Diane. Thanks